- Home

- Phillip Grizzell

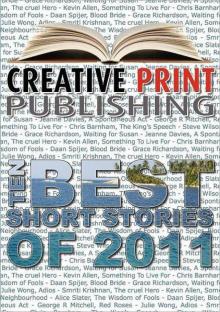

Creative Book of 10 Best Short Stories

Creative Book of 10 Best Short Stories Read online

THE

CREATIVE BOOK

OF

TEN BEST

SHORT STORIES

2011

Creative Fiction

First published in 2011 by

Creative Print Publishing Ltd.

Copyright ©

Copyright to each story rests with the author of that story.

The Introduction is copyright to Creative Print Publishing Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner.

ISBN-978-0-9568535-5-4

LIST OF CONTENTS

Introduction 4

Our Neighbourhood Alice Slater 5

The Wisdom of Fools Daan Spijer 10

Blood Bride Grace Richardson 22

Waiting for Susan Jeanne Davies 32

A Spontaneous Act George R Mitchell 40

Red Roses Julie Wong 52

Adios Smriti Krishnan 63

The Cruel Hero Kevin Allen 74

Something to Live For Chris Barnham 80

The King's Speech Steve Wilson 91

Biographical Statements 97

INTRODUCTION

The short story has been round since the beginning of time, told by people sat around fires in the evening spinning their poetic tales. It was a matter of bringing people together as a community to share in the pleasures and passions of a tale well told.

What of this collection?

The stories within come from many countries, we chose the stories we believed to be worthy of this collection, and paid no attention to their origin. Nevertheless, the authors are from the United Kingdom, the United States of America and Australia.

While reading this stunning collection, you'll quickly fall into the feeling that you’re there, sitting comfortable round the community fire, the skies are clear with bright stars, you can almost smell the sweet, hypnotic aroma from the smoldering fire, then drawn deep within the tales unfolding.

Sit back and enjoy.

Creative Print Publishing Ltd

Our Neighbourhood

Alice Slater

Our Neighbourhood

Everyone in our neighbourhood knew Lucy, the working girl with the thick berry-coloured scar. It stretched across her throat, from ear to ear like a sliced melon. It was never quite hidden under the layers of cheap cover-up she piled on. Eventually I think she stopped trying to hide it altogether. I suppose it pays to be known in that line of work.

We saw her walking to town at dusk, her thin ankles strapped into stilettos that clacked against the pavements. We saw her in the supermarket, squeezing peaches between manicured fingers. I always made the children look away. I’m not a prude, but certain things are difficult to explain and are best kept away from young ears.

When her body was found, battered and broken on a grassy verge just outside of town, there was no particular moral furore. If anything, I suspect some of the elderly residences of our neighbourhood were secretly pleased to have one less whore strutting the streets, but that’s just my opinion. She wasn’t local and she had no family nearby, so it wasn’t really our business to worry anyway. She wasn’t our problem: just another bag of loose morals, attracted to our neighbourhood from one of the grottier suburbs. The scar that lassoed her throat proved she was trouble.

When the next one turned up, an unknown wretch with an addiction to methamphetamine, there was very little media interest. She had been throttled in her bedsit, two gloved hands wrapped around her lily-white neck. Everyone assumed it was one of her clients, a dirty deal gone wrong. When she was eventually identified as Maureen Clyde, the local paper ran an article on page twelve, but no one I knew read it. The paper speculated upon a potential connection between Maureen and Lucy but, apart from their wicked trade, the two cases had few similarities.

These girls of questionable moral fibre, they come to our neighbourhood and think the streets are paved with gold. Their sort are always trouble and trouble self-perpetuates. If it didn’t happen here, in our neighbourhood, it would happen elsewhere. We weren’t concerned about our little neck of the woods earning a name for itself.

During the summer fête at the primary school, a third was found by dog walkers on the other side of the river. She had been stabbed in the chest, her left ventricle pierced. She bled to death, alone in the middle of the rec.

Number three was younger than the others, a baby at just sixteen. That, and the violence of the murder caused quite a stir, I can assure you. My husband in particular became quite withdrawn. His sleep suffered and he lost his appetite. I chided him for frightening the children. Sophie was too young to understand, but Michael noticed the change in his father, and it doesn’t do well for a boy to recognise weakness in his primary role model.

Summer was quiet, and it seemed as though the murderer had given up his plight. Sophie rode her first bicycle, a bit of a late starter, but she lacked confidence. Michael had his first shave, running a razor over his soaped peach fuzz under my watchful eye.

It didn’t last, the domestic bliss. We were struggling to keep up with the mortgage payments, and I was working harder than ever to make ends meet. With Christmas approaching, we didn’t have the funds to provide the children with the kind of holiday they’d come to expect: glittery cards for all their classmates, a turkey dinner with all the trimmings, stockings crammed with goodies, a tree that grazed the ceiling, its branches laden with trinkets and chocolates.

I was working so hard, I didn’t have much time to put into our marriage, but despite that, I still managed to perform all my wifely duties, even the unmentionables, with the kind of regularity expected by the average male libido. I administered love, care and affection, as well as allowing him access to the more exotic orifices on special occasions, like birthdays and bank holidays, yet he continued to seem withdrawn, and I wondered if there was somebody else. He insisted it was just the spat of murders. They worried him, he said.

I found out the hard way that he was right to worry. It was about eleven thirty on a Friday night. I took a mini cab, even though it’s only a ten minute walk. It’s not safe for a lady to walk the streets late at night, even in our neighbourhood. The concierge didn’t bat an eyelid as I walked through the hotel reception, perhaps because I only wear designer suits to work. I like to give a very particular professional impression.

The client was white, middle-aged, a sufferer of erectile dysfunction. I suspected he just wanted a bit of female company and at £200 an hour, I was more than happy to oblige. I managed to coax an insipid erection from him, destined for an inevitable flaccidity before it was even half stiff.

We spent the last fifteen minutes talking about gardening techniques whilst I pinched my nipples and writhed on his lap. He tugged himself into an orgasm that hardly seemed worth the bother, but it’s not my place to judge. Men do have some terribly unorthodox methods of getting themselves off.

The other girls were street urchins, drug addicts, scum. I was none of those things. I was a business woman. I worked for myself, at the best hotels our neighbourhood had to offer.

Like the villain of a horror film, he pulled a knife and held it high above his head. It flashed towards me, but he missed, instead slicing through the peach of my cheek. Blood splashed onto the pillows, and I screamed. Footsteps thundered down the hallway and, in a panic I suppose, he ran.

The scar goes from just below my left eye right down to my jaw.

Everyone in our neighbourhood knows me now.

The Wisdom of Fools<

br />

Daan Spijer

The Wisdom of Fools

His Worship, Robert Anthony Dewcliff, sits behind his large desk in his private chambers, behind the East Beach Magistrates Court. He is leaning back in his chair, his hands clasped, except for his index fingers which form a ‘steeple’; this he taps against the tip of his nose as he contemplates a photo in a plain timber frame on his desk.

The subjects of the photo are dressed formally, as if they are about to go to a ball. It is an obvious studio shot, with a painted background of a formal garden.

The photo dates from the late 1940s. One of the women, seemingly in her mid-twenties, has a child of around five years on her lap. The child is the infant Robert Dewcliff and the woman is his attractive mother. Others in the photo are his father, grandparents (both sides) and his great-grandfather.

Robert Dewcliff focuses on the grey-haired old man. He is the reason for Robert Dewcliff’s feeling of misery right now – it was the old man’s unrelenting control over his son and grandson that has led inexorably to his great-grandson’s current mood.

The bad mood is also, perhaps more directly, the result of this particular morning’s proceedings. Robert Dewcliff called for an adjournment well before the scheduled lunch break, as he felt the tide of misery flow over him. He could no longer listen to the interminable rubbish which the witness was putting forward as sworn evidence.

He studies his great-grandfather’s face again. The eyes stare straight at the camera, challenging, daring it to disagree with the subject. Even in this monochrome, it is easy to imagine the cold blue of those eyes, and the slight ruddiness of the cheeks. The hair, thick even in his late seventies, is obviously grey, as is his well-trimmed beard. His shoulders are held square and his chest slightly puffed out.

Robert Dewcliff’s gaze slides across to the image of his paternal grandfather – a slightly less severe and younger copy of the old man. And then to his father, not looking at the camera, but slightly to his right, as if waiting for instructions from the two older men. Robert’s father, now in his eighties, still often looks as if he is waiting for instructions.

Robert Dewcliff’s mood and premature adjournment are the result of the evidence given by one Fabio Retsino, of how he has ended up in his life of petty crime because he has refused to follow in his father’s and grandfather’s footsteps.

Robert Dewcliff has often fantasised about refusing to fulfil his family’s expectations, but he has lacked the courage. He has always wanted to be a clown. As a child he watched, fascinated, the antics of the painted men with the loose clothes and huge shoes, every time he was taken to the circus. He decided then that he wanted to make people laugh and be paid for it. As a child he was good at acting the fool and he was richly rewarded with attention and sweets and hugs and pats on the head.

When he told his father that this was what he wanted to do for the rest of his life, his father laughed (at first) and then grew stern and lectured young Robert on responsibility and upholding the family tradition. When he approached his grandfather, he was surprised at the vehemence of this kindly old man’s response.

“Absolutely out of the question, young man! I’m surprised at such foolishness! I will not allow it!”

When Robert persisted in talking about it, it was made clear by both men that he would not get a cent from the family unless he went on to study law. In fact, there was a hint from his grandfather that his father may even be kicked out of the firm if young Robert did not fall into line.

Robert Dewcliff closes his eyes and sighs. Would he have ended up like Fabio Retsino if he had followed his heart? Would the difficulty of making a living have cast him into criminality? It is very likely that this was the fear held by his forebears – that there would be a throwback in the family to past, illicit activity.

And here Robert Dewcliff sits, on the other side of the duality.

His ancestors had been fine, upstanding citizens, making a living from the fact that lawlessness was rife in 18th Century France. The men were turnkeys in some of the largest gaols – they had been for generations. Their very name indicated this: du Clef, the ones holding the keys.

How easily a coin can flip. One moment his ancestors were at the head of their profession, the next they turned tail. Gerard du Clef, head of the family in pre-revolutionary France, said he smelled it in the wind, that it would become unsafe for them. The turnkeys left with their families and settled in England, most of them in London. Unfortunately there was no ready market for their specialised profession and they found it extremely difficult to survive, let alone live in a manner they were used to.

Gerard found work in a hospital and a small number of the other men managed to find work. However, Gerard’s son, Michel, decided to make good use of the knowledge he had gleaned from the prisoners under his care in France, and embarked on a career which involved relieving those who had more than he had, of their surplus. Michel was at heart egalitarian. The fact that he eventually owned more than most of those around him seemed a point lost on him, until he himself was burgled. He made the mistake of complaining to the authorities. They, in turn, went about their business thoroughly and questioned his large collection of valuables. His explanations did not stand up to scrutiny and Michel found himself behind locked doors.

He was not the only member of the once respected family to find himself eventually shipped across to a godforsaken land halfway around the world. He was at various times a resident of Van Diemen’s Land, Norfolk Island and Sydney Town. Ironically, through good behaviour, intelligence, ingratiation and good luck, Michel du Clef became an assistant to the governor of one of the colony’s gaols. He was in his element. Although he had a wife in London, he knew he would never see her again, and at the age of forty-three he married Mary Elizabeth Pointer. They had eight children, seven of whom survived into adulthood. Michel remained a functionary of the gaol system. Two of his sons took up the law and that tradition was kept alive from father to son through to Robert Dewcliff.

It is a heavy weight on Robert’s psyche. While he mostly enjoys his work, he often feels that something is missing in his life. As a compromise, he tries to instil some lightness, even humour, into his Court. However, it is not the same as being a clown, with a painted face and red nose and an appreciative audience laughing uncontrollably.

Robert Dewcliff stands up, stretches and yawns. He cannot keep those in the courtroom waiting any longer. But how can he ensure that some sense of justice comes out of this case? He gives three light taps on the door leading into his end of the courtroom.

“All rise!” The clerk of Courts bellows this out in his strong, rich voice.

The door at the front of the Court opens and Robert Dewcliff comes through and takes his seat on the Bench; everyone else then sits down. He looks around the courtroom. The Prosecutor (Alan Appleby) flips through his notes; Retsino’s solicitor (Clive Johnston) is turned in his seat, in conversation with his client; Retsino several times looks up uncomfortably at the Magistrate; members of the public are shuffling in their seats, or talking quietly.

Robert Dewcliff clears his throat. “Stand up please, Mr Retsino.”

The Defendant gets to his feet, with unease showing on his face. His solicitor also stands up and addresses the Magistrate. “With respect, your Worship, I feel it is improper that you should have decided this matter already without having heard all the evidence my client wishes to call.”

Robert Dewcliff motions to the solicitor to sit down. “I have not decided anything yet, Mr Johnston.”

He then turns his attention to the Defendant. “I am not too interested what family tradition you did not want to follow, Mr Retsino. But I am interested to know what career you wanted to follow, instead of which you ended up before this Court.”

The Defendant blinks and hesitates. “Well Sir, I wanted to go to university and my dad said that I was trying to be too hoity-toity. He said that I was letting down the family and that was I too proud to be a clown.�

��

“Were your parents clowns, Mr Retsino?”

“Yes Sir.” The Defendant looks uncomfortable, even embarrassed, at this revelation.

Robert Dewcliff’s jaw drops as he stares in disbelief at the man standing before him. Then he starts to laugh… a full-bellied laugh, which echoes around the courtroom. Everyone’s eyes are on him, most faces expressing disbelief. Several people start tittering.

The Clerk stands up and is about to call the Court to order, but Robert Dewcliff waves him to sit down. He is still chuckling. “It is okay, John. It is just too ironic. I will tell you about it over lunch.”

Creative Book of 10 Best Short Stories

Creative Book of 10 Best Short Stories